From Peptide Binders to Small-Molecule Leads: How Receptor.AI Approaches Translation

Announcement

Full Text

Peptides often provide the most informative starting point on challenging targets: they show where charge, hydrophobic contacts, and local flexibility really matter for binding. But strong peptide binders rarely turn straight into viable drugs. They typically run into permeability, stability, or manufacturability limits, while parallel small-molecule programs on the same target may struggle to find any usable pocket at all.

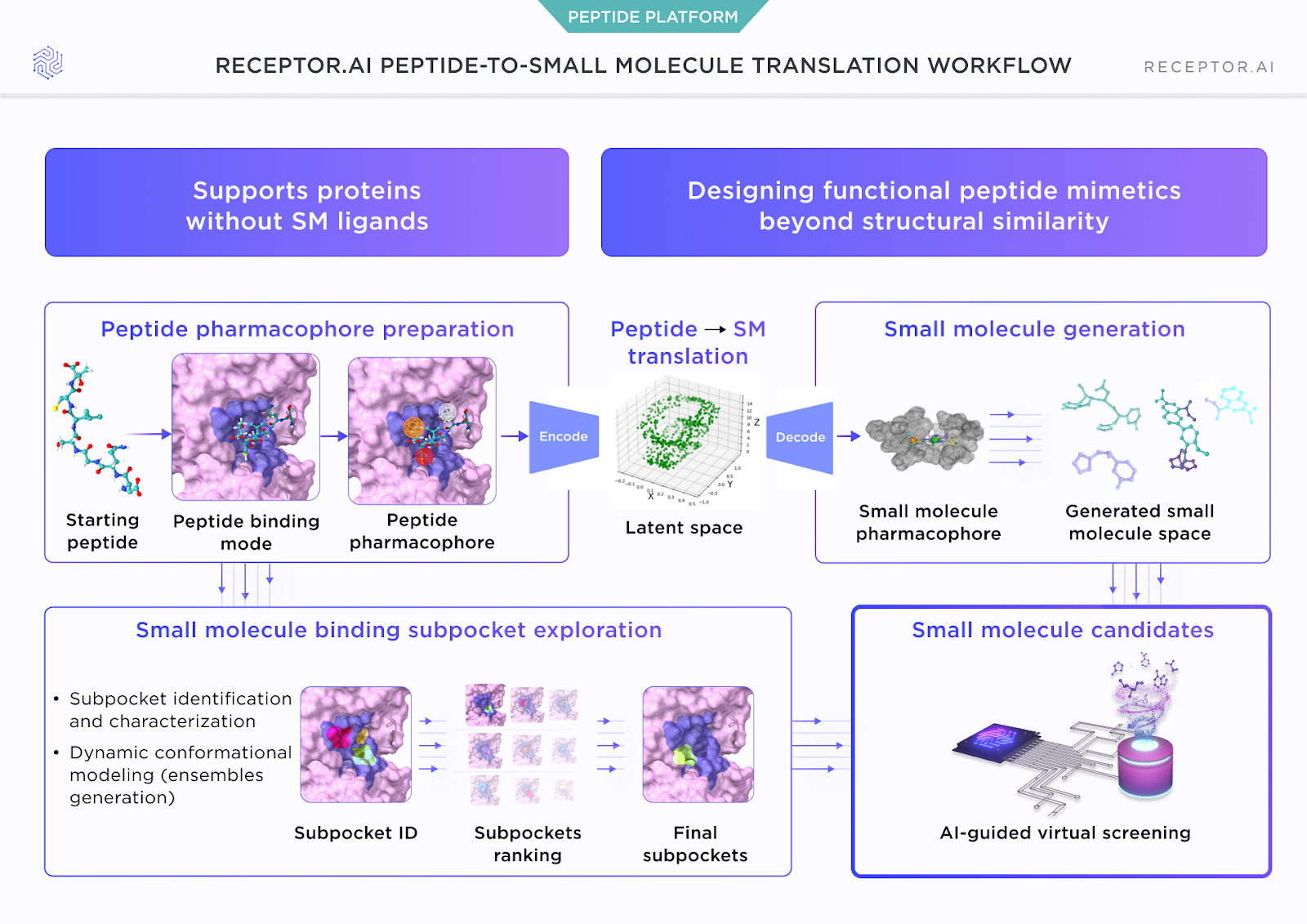

Our peptide-to-small-molecule (pep-to-SM) workflow is built to operate in that gap. It treats the peptide–protein complex as a functional blueprint and uses it to design small-molecule mimetics that retain the key interaction logic but occupy more drug-like (or at least developable) chemical space. The aim is not to “shrink the peptide”, but to rebuild what matters in a new, tractable scaffold. Because we start from peptide binders rather than existing ligands, this approach naturally supports proteins without known small-molecule ligands and focuses on functional peptide mimetics rather than strict structural miniaturisation.

What we mean by pep-to-SM translation

For us, pep-to-SM translation is not about copying a peptide backbone into a smaller scaffold. It is about extracting a functional pharmacophore – the minimal set of interactions that truly drive binding – and rebuilding those interactions within a small-molecule framework under realistic ADME and developability constraints.

Concretely, this means:

- Start from a real complex. We use a peptide–protein structure (experimental or genuinely high-confidence) to define the peptide binding mode.

- Extract a peptide pharmacophore. We identify which residues form essential electrostatic, hydrogen-bonding, π, and hydrophobic contacts, and which primarily act as spacers or structural elements.

- Move into a learned (“latent”) representation. That pharmacophore is embedded into a representation that no longer depends on the peptide backbone: it describes what needs to happen in the pocket, not how the peptide achieves it.

- Decode into small-molecule hypotheses. We generate small-molecule pharmacophores and scaffolds that can reproduce those interaction roles with feasible molecular weight, polarity, and synthetic complexity.

In short, we preserve the interaction logic while allowing the underlying chemistry to change completely.

Why naive peptide-inspired design often fails

In peptide-inspired small-molecule projects, we repeatedly see two failure modes.

The first one is mimicking volume instead of anchoring subpockets

Teams start by overlaying the 3D outline of the peptide and trying to reproduce its overall volume. In practice, this ignores two key realities:

- the charge distribution and hydrogen-bond network that need to be preserved across relevant conformations, and

- the need for at least one discrete, rankable subpocket where a small molecule can actually anchor.

Without that subpocket focus, designs either track the peptide’s shape but lose the right electrostatics and dynamics, or they drift toward excessive polarity (to keep every contact) or high lipophilicity (to claw back potency on a flat surface). The honest conclusion in some cases is that the interface simply doesn’t offer a robust small-molecule foothold.

The second one is over-reliance on a single structure

Designs are optimised to one crystal or cryo-EM frame. When side chains shift, loops move, or a cryptic cavity closes in a different conformation, the assumed binding mode disappears. What looked like a clean pocket in one frame turns out to be transient or artefactual.

Our workflow is built to surface these limitations early – including cases where translation is unlikely to succeed – rather than after multiple rounds of synthesis.

How the Receptor.AI workflow works

Our internal peptide-to-small-molecule translation workflow includes: peptide pharmacophore preparation, subpocket exploration, actual translation to small-molecule pharmacophore, small molecule generation, and AI-guided virtual screening.

1. Peptide pharmacophore preparation

We start from the peptide–protein complex and its binding mode, then construct a peptide pharmacophore that captures which interactions are required for affinity and, where relevant, selectivity within a target family.

Where available, we incorporate experimental information (mutagenesis, alanine scans, SAR on peptide truncations or substitutions) to confirm or adjust the pharmacophore. Residues that consistently tolerate changes without loss of affinity are treated as spacers or structural supports; those that are essential are encoded as mandatory interaction features.

2. Subpocket exploration under molecular dynamics

Around the peptide contact region, we run subpocket identification and characterization using conformational ensembles rather than a single rigid structure. The goal is to distinguish:

- Stable pockets that persist across relevant conformations

- Transient pockets that appear only occasionally but may still be exploitable

- Artefactual pockets that disappear once dynamics or solvent are treated more realistically

Subpockets are then ranked by how well they can host fragments that realise the pharmacophore without forcing unrealistic size or polarity.

3. Pep-to-SM translation in latent space

We embed the peptide pharmacophore into a learned representation (“latent space”) that captures which arrangements of interaction points are compatible with the binding site. From this representation, we generate:

- Small-molecule pharmacophores that preserve the key interaction roles

- Scaffold hypotheses that can implement those roles in a chemically tractable way

These designs are constrained to stay within appropriate physicochemical ranges for the problem at hand – including beyond-Rule-of-5 territory where the biology demands it, rather than forcing everything into a traditional small, flat Ro5 model.

4. AI-guided virtual screening and triage

Around these scaffolds, we build focused small-molecule libraries. Candidates are:

- Scored for subpockets fit and pharmacophore satisfaction across the conformational ensemble

- Passed through ADME and liability filters (permeability, polarity, basic stability, structural alerts)

- Prioritized into a tractable compound set for synthesis rather than a long undifferentiated list

As experimental data come in, we update the working pharmacophore, adjust how we weight different subpockets and interaction hypotheses, and re-rank subsequent designs. Later cycles are therefore increasingly shaped by project-specific SAR, not just generic priors.

The result is a targeted search around a peptide-defined interaction pattern, rather than a generic virtual screen over millions of unrelated compounds.

Where this sits in our broader platform

Pep-to-SM translation sits at the junction of our peptide and small-molecule capabilities:

- On the peptide side, we model complex, often PPI-like interfaces and extract the underlying interaction logic from peptide binders – including cases where no small-molecule ligands are known.

- On the small-molecule side, we generate, dock, and triage chemotypes that can implement that logic under realistic developability constraints, with explicit attention to permeability, polarity, and chemical tractability.

For teams with well-characterised peptide binders but a preference for small-molecule drugs, this is where we can add value: turning a peptide binding mode into a set of small-molecule starting points, with a realistic view of when that translation is likely to succeed.